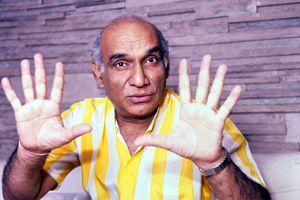

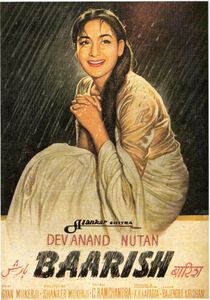

My first impression upon viewing Raj Kapoor’s mythical Satyam shivam sundaram, an impression shared by many other bloggers, is that the Showman

had purely and simply been manipulated by his lecherous pulsions, and had also manipulated us spectators! Gone are the days (I told myself) of the virtuous Vidya (Shree 420), and nobody buys his “real beauty is inside”

formula while watching Zeenat Aman’s gorgeous and exposed charms. On the contrary, everybody thinks: oh well, since it’s cinema, let us at least enjoy the show. Who cares about the message (check

here)? And so it all comes down to: mmm, she’s really tasty. Or if

you’re a Shashi fan: he’s certainly dishy too (personally I think he’s rather pathetic, but as you guessed, I’m not a Shashi fan).

I was therefore in a classic suspension position, where I lazily followed the story and its avowed narrative intentions, while really ogling what RK was serving me under the pretence of a preachy and bungled story (you can read it on Nida’s blog – she has also very pics, thanks Nida!). It’s true that the sexual revolution, at the time (the film dates from 1978), was in need of good exponents, and perhaps such a revolution was necessary (thought I)… At any rate, Zeenat Beebie did it! Many people remember about SSS nothing but the missus’ curvy bronze flesh (I don’t mind saying I also find it very pleasant).

But there’s something (mostly in the first half) that woke up the dozing art critic: many scenes are placed in a timeless atmosphere, now oneiric (or psychedelic), now mythological, and so the reading of whatever happens can be interpreted along other lines. If indeed the story is no longer only that of Rupa and Ranjiv, but of a more archetypal pair (Krishna and Radha, and why not Adam and Eve, see later), then perhaps the movie acquires a purpose which otherwise one might think was sadly lacking. We’ll come to this in a minute.

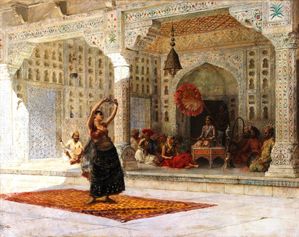

Eyes wide shut

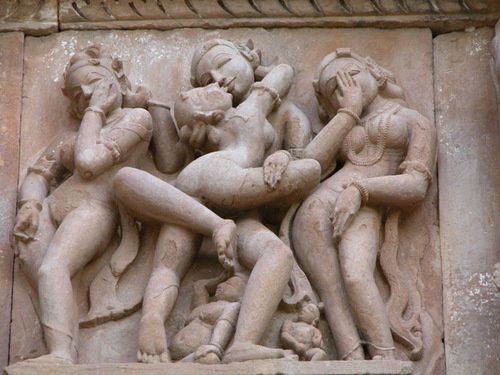

Also, while watching the movie, I couldn’t not think of a paradox which I have already met about Indian culture: why is the country so generally prudish on the one hand, and yet so free when it comes to celebrate the beauties and bliss of human loving? In the film, we see Rupa caressing the religious stone (Shiva’s lingam) in a very sexual way, but the tantric traditions of Hinduism also seemed to include a sexual dimension which didn’t pose problems to practitioners. At Khajuraho (below), among other places, such open acceptance of sexuality and eroticism is made clear. Could the film be seen, then, as a celebration of sensuality and innocent sexuality? Apart from the fact that such a possibility rings very much like a westernized perspective of Indian tradition (see The householder), the story doesn’t help a lot to uphold such a view, and we all know how easy it is to hide behind such pretexts.

So, what was left to save the film from cheap voyeurism and kinky grooviness? Well, in fact, luckily, quite a lot. The second part of the film, where we see Rajiv reject the Rupa he hates to look at in order to join and love the Rupa he thinks is the only true one, contains a promise of symbolism, for example the fact that Rajiv, the dam engineer (= the restrainer of natural forces) has to face the overflowing of truth coming from a pent-up source which he has been responsible in barricading. One can read the breaking of the dam and subsequent flooding of the downstream lands as the destruction which Rajiv brings about by sticking to a false picture of feminine value. By refusing Rupa as she really is, i.e., supposedly innocent and God’s creation, he brings about divine wrath and will need to save her from his own hubris. They accordingly end up atop the redeeming temple! Anyway Rajiv seems to be RK’s personal target – I wonder if lil brother minded! Remember how he divests him of his shashilicious hair under the waterfall shower?! What was left was just a few black sprouts in the middle of his chest – enough for the enamoured village girls, but for us?

Then we also have this strange opposition between the two sides of the same woman as represented by the two Rupas. Perhaps Raj Kapoor wanted to show that certain men harbour a schizophrenic image of femininity, and Rajiv (poor Rajiv) could then be seen as the picturization of this masculine tendancy to love and hate Woman at the same time. Under this perspective, Rupa’s scar might stand for the various wounds which affect idealized beauty as dreamt by romantic and passionate lovers, the most obvious of which would be childbirth and the transformation of the woman’s exclusive femininity into the shared condition of maternity and family life.

But more fundamentally, I think some men are deeply insecure (if not terrified by) about women, and women’s relationship to life and death (symbolized by

menstrual blood), and cannot relate to them beyond this idealized picture they have of their mother. Rajiv would then excessively represent this type of infantile men, keeping in mind that all

men probably have some trouble with their representation/fascination of women, or at least have to fight against forces within themselves and to replace fantasies by reality. Many men are

apprehensive of femininity and maternity, and hopelessly long for a eternally youthful figure which doesn’t exist.

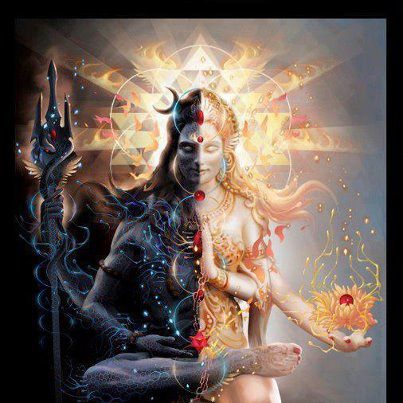

In the first half, we have the allusion to Radha and Krishna’s relationship, with Rajiv representing a dark Krishna, whose

darkness (goes Rupa’s story) is caused by Radha’s black eyes. Zeenat Aman’s eyes are indeed black, but her skin is darker than Shashi Kapoor, which makes the whole situation rather funny. But to

stick to the mythological frame, or perhaps not to stick to it, I have found (here) this quirky picture of “tantric marriage” with a half black, half bright Shiva figure:

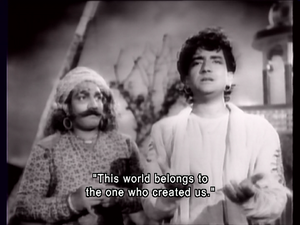

and it is said in various places (one such) that the film’s title is a designation of Shiva: Shiva in the Hindu pantheon is the Destroyer. What Brahma creates and Vishnu preserves, Shiva wipes out so that creation can start again. Now this divine cycle must be in coherence with the human cycle of birth, life and death. Death in such a cycle isn’t only understood as a negative force of destruction, but as a positive one of transformation so a new life can flourish. In the film, Rupa and her scarred face figures this necessary deathly process: Rajiv sees in her not only an ugly and unfortunate girl, but he’s shocked by what is really a death-face (and even more precisely a death-in-life face).

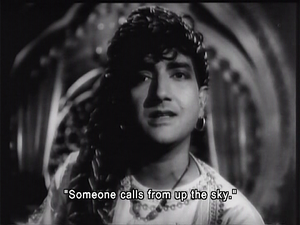

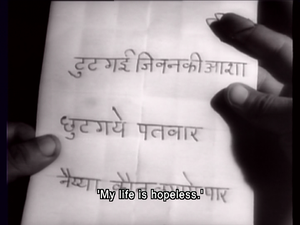

What he sees in her nobody else sees; this horrid decomposing skull is a visualization of a transformation, the mutation of beauty into horror, of grace into evil, because it is seen through Rajiv’s fears. I believe nevertheless that Raj Kapoor doesn’t want us to adhere to his prejudiced hero. His negative reaction is the reverse side of the teaching which he will accept later on in the movie. The painful vision contains a truth (Shiva’s truth), which, unpleasant as it is, must be confronted: all flesh, all beauty decomposes ultimately and becomes ugliness and horror. And there is something even more unpleasant in that it is connected to feminine beauty, because women are the carriers of human life. So when he sees Rupa (a word which means beautiful) for the first time, he exclaims:

This question is the movie’s whole question. He asks her (twice) “Kaun ho tum?”, and not aap (the polite form), indicating that he is still sufficiently intimate with the different person he believes he is facing. He might of course, as a dignitary, say tum to all women, known to him or not. But anyway what’s clear is that he faces somebody who is both looking like Rupa and enough different from her for him to reject the identification. One line of scenario might have been Rajiv’s breakdown upon realizing that his one and only Rupa is defaced. But what happens is altogether different. He is confronted with a stranger, Rupa’s disfigured twin so to speak, Rupa’s negation in a way. Rupa’s evil double. Symbolically, the moment her veil is up, Rajiv is confronted with a truth (there’s no veil any more) which is death, and he can only refuse it at first. It will take the rest of the film for him to accept this truth, ie, that his beloved and her deathly appearance are one and the same (divine) reality.

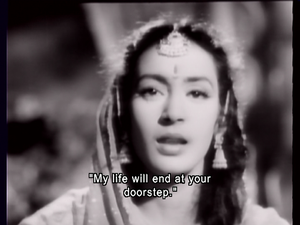

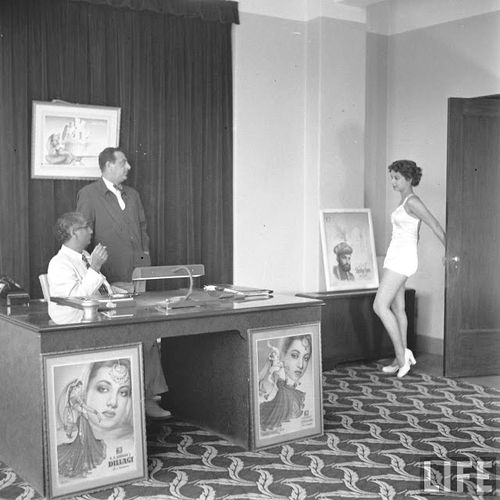

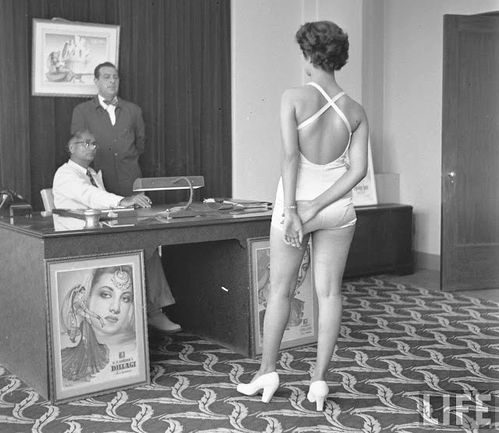

The Apsara

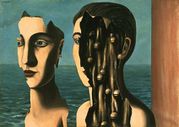

It’s normal that Rajiv, because he has seen in Rupa Shiva’s destructive power, should feel such a jolt and revulsion. The story turns him into a sort of visionary, and Rupa’s veil becomes the symbol of what hides her mystery to the rest of humanity. She symbolises the womanly forces of life and death, the Shiva-cycle present in the human race. One could say that’s her truth (satyam), but this divine (shivam) aspect makes it fitting for Raj Kapoor to have chosen a very beautiful (sundaram) representative such as Aman. On the other hand, all women are concerned by this male tendency to sense in them more than just their counterpart. Look at these paintings by the Belgian painter René Magritte:

Wouldn’t you say he has represented something of this male complex? Doesn’t it seem that he has understood that for men, women are a scary power and a mystery, and that they (the men) need to be reconciled with them? I am also reminded of the classic associations of women and death (this is a mental structure, of course, please all ladies reading this, don’t assume I am making a statement about the reality of women!) through such artistic symbols of Death and the maiden, and to come back to RK’s movie, there’s the theme of the casting of the spell, which again goes back to Woman’s phantasized destructive power upon men. The question “who are you?” resonates against this background. It corresponds to this fear within the masculine psyche of a feminine power linked to life and death, and feminine seduction as a threat to his integrity, to his own power and pleasure.

I said I would volunteer a word about Christian mythology, which as I well know, shouldn’t perhaps be brought about here, seeing as we are clearly in a

Hindu environment. My defense nevertheless is that I believe there are universal archetypes that can bring together different cultural ensembles, and it seems to me that Satyam shivam

sundaram presents us with a readable (if limited) Adam & Eve motif. Both lovers meet in a sort of primeval, ideal garden, where clearly realism is sacrificed to make us understand that

the place is a projection (this is what we have in the Genesis). The waterfall (above) could well speak of the Fall itself, and Rupa’s deformity could be seen as the curse for her sinful

act. And let’s not forget Eve is the instrument by whom death inflicts the human condition according to the Bible. Well, even if these parallels shouldn’t be strained, the film’s evocative

folktale symbolism suggests associations which in themselves make it more interesting, especially in this case!

All in all, the movie, with its often underlined flaws, contains enough symbolism for us to say something about RK’s attitude to women and cinema. He’s not here to answer any more, but I would have liked to ask him the question: how much has the cinema (this maya, this art of illusions) taught him about women, and how much has he lost through unreined desire and experimentation? I had already tried answering this question in Sangam, but it’s also posed again here, even if through the filter of allegory. I’d say that what he’s gathered in terms of art has been tremendous, but probably to the detriment of his peace of mind.

Here are some reviews (on top of those already quoted) which I selected for their thoughtful remarks: Adeline’s (in French), Beth, who watched the movie with Carla, and not forgetting Philip’s short but insightful comments. And there’s a comic take at P-pcc.blogspot!