I’d been wanting to watch Baarish (1957, Shankar Mukherjee) for a long time, but as there were no subtitles, I knew I was in for a more strenuous viewing than usual. Still, this film was a little like the missing link in my Nutan experience! It’s a pleasant movie, inspired, I think, of Kazan’s On the Waterfront, which explains why we have all those kabootars in it (Sunheriyaadein was wondering… BTW, thanks to that blog’s author for the story!), but also accounts for the film noir atmosphere. The only important aspect Baarish doesn’t adopt is the character of the Catholic priest, Father Barry. But otherwise, there’s Ramu the young thug (our lovable Dev Anand), his purifier Chanda (equally lovable Nutan), Ramu’s brother, and the Underground Boss, who in Kazan’s film was played by the fearsome Lee J. Cobb, and who’s Jagdish Sethi here. Please do as I did, go for the full story at Sunheriyaadein’s blog. Oh, don’t worry (s)he stops at the right moment to leave the suspense intact in your mind…

Baarish of course is a showcase for the two lovable ones: it’s here to entertain their fans and guarantee their interest will be sustained for two hours. It did that for me very effectively! When Ramu, sent by his brother, arrives in Chanda’s village, for example, everything’s exquisite from the start: she’s perched in a tree, spits, pouts and tinkers with monkeys (see A nutty Nutan, where a number of caps come from this scene). He frowns, glares, and pretends a lot. Apparently she believes he’s some kind of tax officer, and she’s going to do her utmost to divert him away from the house, all this to the tune of Yeh muh aur daal masoor ki. She tries by scowling at him, which doesn’t work, then she writes a false message near the entrance door (“all gone to Kashi – back next year”), but Ramu can’t read (he supposes their names are written), and finally she locks the door on him, but he peeps through from above, and spies on her! All this is delightful, and gloriously funny thanks to Nutan’s comic talents and Dev Anand’s Gregory Peck-like charms. Communications-wise, they actually bleat at one another!!

The rest of the film is very predictable, because it plays on the various moods necessary for the fan base to appreciate their heroes from the various classic perspectives: after the opening distrust, we have the love scenes, then comes danger, and there’s a great moment when Nutan is seen through the besotted eyes of the village suitors: whereas they look at her, busy drawing water from the well and waiting for her pail to fill, she suddenly becomes a dovey-eyed belle who’s entranced by their singing and trite words, comes closer to them, lends her cheek to their lips, and then, bubble-like, springs back into her previous form as the incensed maiden who’s straight out from Seema! The scene is also an opportunity to laugh at human faces, brought together as in some Rembrandt or Leonardo paintings. The film, BTW, is full of them:

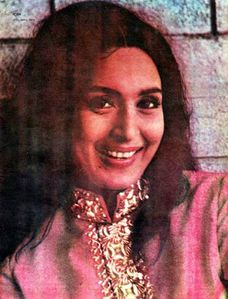

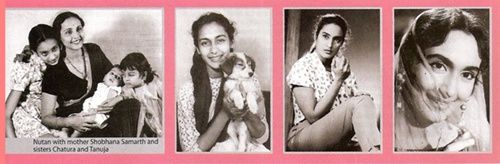

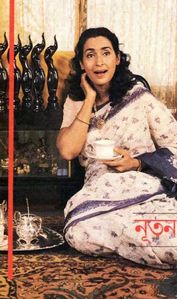

I think Nutan was still busy asserting her actress’s skills, and her physique enables her to perform masterfully: she had a face she could twist into grimaces, and which could also melt into any smile! It’s a pity that the Youtube version seems cut at certain points, for example we don’t get to see the precise moment when the pair make up… A real pity, because if this moment exists, it would have been very interesting to observe! Nutan’s youthfulness as usual makes one shrink in utter wonder. I don’t know whether that “kind of well-endowed” nature, “with her puppy fat” (as Sharmi playfully suggests) has anything to do with it? I’d say yes, because her ravishing face had a fullness and a pliableness then which turned into a more straight and longish type of features later in life. Have a look:

What’s absolutely wonderful is her impersonations of loving motherly feelings in this film. I don’t remember if this struck me as powerfully in other movies. I strongly believe that Nutan’s femininity expressed itself very deeply in her motherliness. Here she hears about children for the first time:

And here she tries to make Ramu understand she’s going to be a mother:

She does it almost without being able to tell him in so many words – she believes in her joy that the man she loves and who has enabled her to become who she wished so very deeply to be, will understand her, understand the change which isn’t one, because she’s always wanted to be a mother, but which is a fantastic change nevertheless, because it’s finally real:

And then the scene where she ties herself to him by smearing on her forehead some of the blood from a wound he got in one of his scuffles (he reprimands her for doing so – I wonder if he means it could be a bad omen, which her love had disregarded?):

And finally that lovely moment of bliss when she realizes she’s finally secured her lover:

Nutan was at the height of her charms - when wasn’t she? - that lanky body which her relatives complained about, or so the legend goes, being then beautifully fleshed out. Later she thinned, and her face became more grave, more interiorized. During the late 50s her fuller shape corresponded to the generous feelings which appeared on her features, and it starts in Baarish. The downside is that her skills were still a little unhoned, if one compares with her Bimal Roy roles, for example. In Baarish she excels at expressing outrage and irony, and a little less grief and loss, as in Bandini or Sujata:

As for Dev, I agree with Sharmi, he wasn’t yet “the charismatic debonair who made all of us weak in the knees”!! His almost British phlegm had not yet become his trademark. He was still a little too brittle, a little too hurried. But then later (very British-like!) he buttoned all the shirts he wore! So yes, I don’t mind saying it was rather cool to see him shirtless and to swagger about in front of a demure Nutan who didn’t seem to notice ![]()

See the rest of the film's photos here